Agyen Kennedy1; Agyei-Ohemeng, J Asamoah, F. B. 1; Richard Obour1 and Bright Adu Yeboah2

1University of Energy and Natural Resources, School of Natural Resources, Department of Ecotourism, Recreation and Hospitality Sunyani, Ghana 2University of Texas San Antonio, TX, USA

| ARTICLE INFORMATION | ABSTRACT |

| Corresponding author: E-mail: james.agyei ohemeng@uenr.edu.gh Keywords: Sampling Surveys Biodiversity Equilibrium Dominance Received: 11. 05. 2023 Received in revised form: 01.06.2023 Accepted: 02.06.2023 | The study was undertaken in Kakum, National Park of Kakum Conservation Area Ghana in the wet season 2022 to identify birds and determine their distribution based on their foraging habits. Using both purposive and convenience sampling, transects and surveys, birds were counted by Point counts and opportunistic surveys All birds were observed at a fixed location using an Opticron Polarex 8×40 binocular and identification of bird species were confirmed by birds of Ghana and recorded vocal reply of birds. Birds coordinate and location was taken at all station using a Gramin GPS device. The results were documented and analyzed in Microsoft Excel 2016 and presented in graphs. A checklist of identified birds’ species was produced with reference to Birds of Ghana. Arc Map (Arc GIS 10.3) was used to plot the locations of species and survey points on the map of the study area. Ten categories of feeding guilds were identified. An Anova test result from the study indicates a p-value of 0.976, showing that there are no significant differences among the birds’ population in the various communities. Family Ploceidae an insectivorous birds dominates the population in the study area. Insects are known to be favored by moist conditions and dense foliage, which is characteristic of the Kakum Conservation Area, hence insects being a ready source of food for birds. |

INTRODUCTION

Avian biodiversity is an essential component of our planet for providing various services to ecosystems like seed dispersal, aesthetic beauty, biological control and environmental cleaners. Their bright colors, distinct songs and calls, and showy displays add enjoyment to our lives and offer an easy opportunity to observe their diverse plumage and behaviors (Khan et al. 2012).

Birds are the only chordates in the Class Aves of the Phylum Chordata, with more than 10,000 species distributed around the world from the Artic to Antarctic areas (Bird Life International, 2012). Birds are important because they maintain the equilibrium of natural systems by pollinating plants, dispersing seeds, scavenging animal carcasses, and recycling nutrients back into the soil.

Additionally, they nourish our souls and our existence on the earth. In some ways, man is dependent on the ecological services that birds provide, making us dependent on them. Globally, people are rapidly destroying ecosystems, particularly in the tropics, which is causing a sharp decline in biodiversity. (Laurance et al. 2002; Dirzo, & Raven, 2003; Lindenmayer, & Fischer, 2013).

The concept of nature conservation is sometimes viewed as something that occurs “out there” in protected areas rather than as an essential part of daily living. The idea that humans are separate from the natural world is reinforced by this viewpoint, which contributes too many of the environmental problems we face today. However, safeguarding biodiversity and ecosystems should be prioritized in public policy, development strategies, and day-to-day activities because they are vital to human society (Hackett, 2015; Kareiva et al. 2011; Lovins, et al. 2001). It implies that we need to comprehend the importance of biodiversity to human society.

Biodiversity is formally defined by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) as “the variety of living organisms from all sources, including terrestrial, aquatic, and other habitats, and the ecological developments of which they are a part; this comprises diversity within species, between species, and between ecosystems.” (UN 1992 Article 2).

An important part of the world’s biodiversity is birds. Birds are the animal category with the most extensive time series of data because of the attention they draw to their behaviors, colors, and songs. Globally, biodiversity is fast vanishing. (Balmford et al. 2003).

The majority of wild animal (Birds) ecology’s economic components have been disregarded, which an issue is made worse by the drop in financing for the fall in instruction in natural history and organismal ecology. (Tewksbury et al. 2014).

For the past 300–400 years, there has been a significant loss in bird habitats, particularly for plants and animals (Decher et al. 2000). There are numerous explanations put out for this decline. Global observations show that habitat changes, particularly in the case of bird populations, are the most frequent cause of population decrease and species extinction. (Mace et al. 2000 According to estimates, habitat degradation was responsible for 36% of all animal extinctions worldwide (Jenkins, 1992).

According to another estimate, over 100 species are thought to go extinct every day as a result of habitat degradation (Ehrlich et al. 1991). Hunting pressure brought on by growing human populations in nearby villages near forests (the fringe communities) and their need for food to survive is another factor contributing to extinction. (Brockington, & Igoe, 2006) concur that humans pose a threat to species.

According to one definition, ecosystem services are “the set of ecosystem functions that are helpful to humans” (Kremen, 2005) There have been extensive investigations on the history of ecosystem services (Daily, 1997; Gomez-Baggethun et al. 2010). The last 20 years have seen a sharp increase in ecosystem services. Governments became aware of ecological services during the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment

(MEA, 2005). (Gomez-Baggethun et al. 2013). The MEA (2005) identified four classifications of ecosystem services: provisioning services, cultural services, regulatory services, and sustaining services, with the goal of evaluating the potential effects of ecosystem change from a human well-being perspective and with an emphasis on ecosystem services. All four categories of ecosystem services are provided by birds. (Sekercioglu, 2006a; Whelan et al. 2008). Both domesticated (like poultry) and non domesticated creatures offer provisioning services. Birds have always been a significant part of the human diet for sport, consumption, and subsistence.

(Moss and Bowers, 2007), particularly waterfowl (Anatidae) and terrestrial fowl (Galliformes) (Peres, 2001; Peres and Palacios, 2007)). Bird feathers provide bedding, insulation, and ornamentation (Green and Elmberg, 2014). Birds provide a crucial focal point for research of cultural services within the ES paradigm because of their special relevance for humans; this is the topic of ethno-ornithology (Clayton, 2013; Podulka et al. 2004; Tidemann and Gosler, 2013). One of the most well liked outdoor pastimes in both the United States and around the world is bird watching. (Kronenberg, 2014a; Ma et al. 2013; Sekercioglu, 2002; White et al. 2014 and has both direct and indirect economic benefits due to the many citizen science initiatives that involve birdwatchers (Greenwood et al., 2007).

Through their foraging ecology, several bird species provide regulating and supporting functions. Scavenging carcasses, nitrogen cycling, seed distribution, pollination, and pest control are some of these services. (Sekercioglu. 2006a; Whelan et al. 2008). Here, we concentrate on regulating and assisting services because the advantages of these services are frequently passed on to people subtly.

Many of the ecosystem services that birds provide are a result of their ecological roles. Thus, estimating their value requires thorough familiarity with the natural history of the species in question. (Sekercioglu, 2006 a, b; Wenny et al. 2011; Whelan et al. 2008). The majority of regulating and supporting services result from resource consumption’s top-down impacts. Birds utilize a wide range of resources in terrestrial, aquatic, and aerial settings. There are over 10,000 species of birds on the planet.

In certain cases, the resource being consumed is a nuisance to forests or agricultural products. In other instances, birds’ use of resources aids in pollination or seed dissemination, encouraging the successful reproduction of thousands of commercially or culturally valuable plant species. Through the numerous Ecosystem Services (ES) that forests and other plants provide, these services indirectly benefit humans. Birds have a significant, global impact on ecosystems through these services Forest fragmentation rate in the country is estimated at 22,000 square kilometers per annum (Hawthorne and Mussah, 1993).

Despite the fact that a large portion of the resource is severely depleted, Ghana’s forests and savanna land still host a diverse range of intriguing plant and animal species. However, it is estimated that more than 70 % of the initial 8.22 million hectares of closed forest in Ghana have been lost (IIED, 1992), and only about 10.9 % to 11.8 % (representing 15,800 to 17,200 square kilometers of forest cover) remain as intact forests. Data on the status of specific plant species are not readily available. Without sufficient action, the country won’t have any intact forests left in a century if things continue at this rate.

The progressive conversion of some forests in Ghana’s middle belts into savannah lands is a sign of the country’s ongoing deforestation. As a result, Ghanaians’ ability to produce goods and earn a living has decreased, and the severe environmental damage brought on by deforestation threatens their very survival (e.g. soil erosion, local climate changes, instability of hydrological regimes and loss of biological diversity). Although most of these are hastened by human activity, their impact on the reduction of the bird population in some sections of Ghana’s middle transition zone cannot be overstated.

As a result, several bird species are in danger. (Ives et al., 2017). There are currently eight (8) endangered birds and 14 nearly endangered bird species in Ghana i.e. species at risk and requiring monitoring. Bird species are the most significant mobile link (Lundberg and Moberg, 2003), top consumers and keystone species in some ecosystems (Raffaelli, 2004); It is impossible to overstate how important they are to ecosystems, and because birds are so widespread in most locations, we also monitor the effects they have on the environment. However, because of the numerous ways in which birds interact with the environment, people can financially benefit from them (Dirzo and Raven, 2003).

Predation and food availability are likely to have an impact on birds (Chace and Walsh 2006). Additionally, seen as key influences on bird habitats, quantity, and dispersion include biological background, agriculture, forest degradation, habitat loss, forest resource use, and environmental contamination. (Borges et al., 2016).

The purpose of ecotourism is to integrate the market driven consumption of goods and services with the mitigation of emissions, ecological destruction, wildlife persecution, and tourism-related effects on biodiversity. this includes observing animals and birding (Isaac et al., 2015).

The activity of identifying and observing birds in their natural habitat is known as bird watching. Both bird’s call and appearance can be used to identify it. Given that they are the single largest category, ecotourism has one of the strongest financial foundations (Cordell and Hebert, 2002).

Tourists can take part in these activities thanks to bird-watcher excitement. Birding is developing into the ecotourism sector with the highest growth and environmental consciousness, and it offers Bird watchers are interest in keeping an eye on the remaining species and learning how new bird species will be introduced to verify their status (Agyei Ohemeng, 2014).

There are over 760 different bird species in Ghana (Brown and Demey, 2010). Domestic birds and other animal species benefit from this, which increases biodiversity. Kakum National Park has roughly 360 different bird species (Dosset and Dosset, 2008). About 40% of Ghana’s total bird population is represented by this. According to Bird Life International in 2005, the Kakum National Park was classified as one of the most significant bird areas in Ghana because of the park’s abundance of bird species in numerous ornithological surveys and research that have been conducted there.

1.1 PROBLEM STATEMENT

Consumption of resources by birds promotes successful plant reproduction in hundreds of plant species by facilitating pollination or seed dispersal. Due to the role that birds play in a variety of natural and human-dominated ecosystems, it is anticipated that these crucial ecosystem processes—in particular, decomposition, pollination, and seed dispersal will experience a reduction (Whelan et al. 2015). An increase in the human population in the outlying areas surrounding the KNP has led to a rise in demand for natural resources, such as land for agriculture, building materials, and fuel wood. Logging and other human disturbances have made these issues worse, resulting in a loss of natural vegetation and the fragmentation of species habitats in KNP. (IUCN/PACO; Deikumah and Kudom, 2010).

Deforestation and forest fragmentation have a direct correlation with species decline in protected areas (Stuart et al., 2008), causing them to colonize new parts including green spaces in cities (Symes et al. 2018). Forest specialists are now being recorded in rainforests, transitional zone savanna, and other dry areas (Agyei-Ohemeng et al. 2017). Most birds choose habitats that are ecologically suitable for foraging. (Agyei-Ohemeng et al. 2017). The monitoring of biodiversity is essential for the sustainable management of the conservation areas in Ghana. Birds as part of biodiversity can be monitored in several ways. One of the many ways in monitoring birds is the study of their feeding habits. Root (1967) defined a guild as a group of species that exploit the same class of environmental resources in a similar way. Thus, guilds point out a functional relationship between a group of species and an ecosystem (de Iongh and van Weerd, 2006).

However, for the majority of ecological biomes, including Kakum National Park, information on the ecological state of birds, their feeding habits, and the diversity of species in their new settings is scarce. (Allport, 1991).

In order to properly manage the avian biodiversity in Kakum National Park (KNP), which is a crucial component of the KNP management plan that is being considered, the study is an effort to document the diversity, feeding habits, and ecological state of birds around the park.

1.2 JUSTIFICATION

This project will provide information that can be utilized to lessen human activities that have harmed bird habitats and to enhance bird viewing in Kakum National Park in some particular settlements. The study’s findings will improve our knowledge of birds and their eating behavior in the ecosystem, promote tourism, improve rural livelihoods, boost park revenue, and contribute to the improvement of biodiversity conservation.

It might also serve as a starting point for future bird-related scholars. It will also be a useful resource for anybody interested in learning more about the birds of Kakum National Park, the tourism sector, the Ghana Tourism Authority, and researchers.

1.3 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

The main objective of this project is to do a checklist of birds in some selected communities around Kakum National Park (KNP and relate them to their foraging behavior habits in order to establish their ecological importance and status.

1.4. SPECIFIC OBJECTIVES

The study will be used to:

- Identify bird species in some selected communities around Kakum National Park.

- Relate identified birds to their foraging habits. • Determine birds’ distribution in selected communities

- Determine the ecological status of the identified birds in the selected communities.

2.0. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Study Area Description

Kakum Conservation Area is made up of two blocks of forests lying adjacent to each other that is Kakum National Park and Assin Attandanso Resource Reserve. They lie in the Upper Guinea forest zone of southern Ghana (Eggert and Woodruff, 2003).

The conservation area covers 360 km2 of moist evergreen forest and also seasonal dry semi-deciduous forest, it receives an annual rainfall of 1,380mm (Csontos and Winkler, 2011). Kakum National Park is located in the Twifo-Hemang-Lower Denkyira District in the Central Region of Ghana. It is located just 33 kilometers from Coast in the Central Region of Ghana.

It lies within longitude 1̊ 5‟ East and 1̊ 2‟ West and on latitude 5̊ 39‟ North and 5̊ 20‟ South. (Fig 1). A study by Wellington (1998) revealed that Kakum Conservation Area has more than five rivers and the main river is called the Kakum River which supplies fresh water to Cape Coast Metropolis and 133 other towns, communities and villages. The river was named after the calling of a Mona monkey (Cercopithicos mona) “Kiakum”. The Kakum Forest, named after Kakum River whose headwaters lie within the park’s boundaries, was originally set aside as a forest reserve in 1925. Although there is a disagreement as to the exact date of their demarcation, they have been ‘reserved’ since the 1930s (Eggert et al. 2003).

Logging, which began in the 1930s, was intensified in the 1950s and continued until 1989 when the Central Region Administration suspended all logging. These two forest reserves are now managed as Kakum Conservation Area by the Wildlife Division of the Forestry Commission. The Kakum Conservation Area was legally gazette as a National Park and Resource Reserve in 1992 under the Wildlife Reserves Regulations (LI 1525) under the administrative Jurisdiction of the Wildlife Department.

The Park was legitimately opened to the general public in 1994 (Twerefo, et al. 2012). The Park is surrounded by fifty-two (52) fringe communities, over 400 hamlets, and over 4500 people. Recreational activities that can be undertaken in the park include; nature walks, bird watching, campsite and tree house, canopy walkway and butterfly watching.

It is inhabited by diverse plant and animal species. It serves as a home for more than five different kinds of globally endangered species of mammals which include forest Elephants, (Loxodonta africana), Bongo (Tragelaphus eurycerus), Diana Monkey (Cercopithecus diana), Black and White Colobus Monkey (Colobus guereza) and Yellow Buck Duiker (Cephalophus silvicultor) (Eagles et al. 2002). It serves as a habitat for over 300 different species of birds and over 100 species of mammals, reptiles, amphibians and 600 different species of butterflies. One of the butterfly species found in Kakum is (Diopeteskakumi) which was originally discovered in the conservation area.

The uniqueness of this park lies in the fact that it was established at the initiative of the local people and not by the State Department of Wildlife who are responsible for wildlife preservation in Ghana (Wellington, 1998). It is also the only park in Africa with a canopy walkway, which is 350 meters (1,150 ft.) long and connects seven tree tops that provide access to the forest.

The canopy walkway was designed by Dr. Illar Muul a Canadian ecologist and was constructed by two Canadians; Tom Ainsworth and John Keelson and was assisted by six Ghanaians who were also experts in tree climbing. The construction took place in the year 1994 and took six months before its completion. The maximum weight the walkway can take is eight tons (8 tons), which is equivalent to eight thousand kilograms (8000kg), this weight is said to be the weight of two forest elephants.

2.2. Experimental procedure

The research was conducted between May/June and September/October, 2021 using Point Count Method (Ralph et al. 1993, 1995a, 1995b). Transects were laid from one community to the other covering four fringe communities in searching and identifying birds using birds of Ghana (Borrow and Demey, 2010).

All birds observed at a fixed location were tallied at repeated observation periods. The fieldwork was carried out in the morning between 6:00 am to 9:00 am, for five (3) stations at regular intervals of thirty (30) minutes each and ten (10) minutes rest to a different station for a total distance of 5 km each, in a compass direction determined on each count day for each week in a month.

Figure 1: Map of Study Area

All counts were done on every Wednesday, Thursday and Friday on the first and third week of the counting months. In all 24 count days were spent counting and identifying birds.

An Opticron Polarex 8×40 field binocular was used to assist in the observation and identification of the bird species. The Gamin GPS device was used to take the coordinate and location of the stations. Nomenclatures of birds were referenced in the field book of birds; ‘Birds of Ghana’ by Borrow and Demey (2010) and vocal replay of birds was used where necessary, especially in the forest where visibility was a challenge for identification. Global Information System (Arc GIS) was used to plot the coordinates of where birds were located on the map of the Kakum National Park (KNP). Every GIS operation was carried out using ArcGIS version 10.3.

2.3. Analysis of Results/Data

All records were documented in a tabular form in an Excel data sheet and the data were analyzed using histogram and statistical methods to determine the diversity of families. We also entered the available data on the conservation, distribution, ecology, and life history of all bird species of the world from 248 sources into a database with >600,000 entries.

This provided us with guidance in classifying the foraging behavior of birds and identifying their families and determining their conservation status. An ANOVA test for significance was used to analyze the variations of birds in the various communities.

3.0. RESULTS

3.1. Species list and feeding guild categorization

A feeding guild is a group of species that exploits similar food resources in a habitat, and its characterization is usually based on the type of food being consumed, which in turn determines the feeding behavior of the availability of food resources.

Foraging guilds can be a useful way to compare changes between species-rich communities because their functional organization can be investigated even if no species are shared. The foraging behavior of birds species based on the Point count method was grouped into various trophic structures to determine the feeding behaviors of different bird species and the food resources of the areas.

A total of one thousand one hundred and sixty-nine (1169) individual birds which were representing one hundred and one (101) species and thirty-two (32) families were observed and identified in the Study Area of Kakum National Park. With the aid of Birds of Ghana (Borrow and Demey, 2010) birds were categorized into insectivores, fruigivores, carnivores, omnivores, nectarivores and granivores. Birds that have a combination of two source of food were grouped into fruigivores- granivores, insectivore carnivores, insectivores-fruigivores, carnivores omnivores, and insectivore-nectarivores.

And those who feed on more than two food sources were grouped considered and omnivore (Munira et. al, 2012). Table:1, shows the various categories of feeding guilds, families and numbers of individual sightings of the bird species.

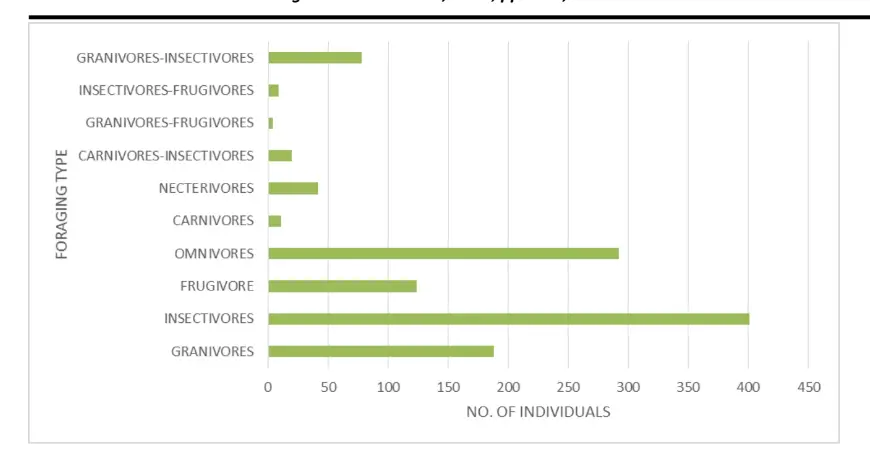

The insectivore feeders recorded the highest number of birds with a total of 401 birds species followed by omnivores with 292 total number of birds. granivores recorded the third highest of bird with a total number of 208 and granivore-frugivore recorded the least number of birds with a total of 4 individual bird species. Figure 3 shows the highest and the least number of birds recorded in the various foraging type.

3.2. Mapping Avifauna Distribution

The GPS data collected from the survey were entered into MS Excel sheet and converted to comma separated values (csvCSV) file format to be read by ArcGIS for the generation of a distribution map, Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Distribution map of birds in the survey area.

Using Table 2 above, an ANOVA test was run to test significant differences among the bird population within the communities.

Table 3 below, indicates that the p-value =0.976, shows that there are no significant differences among the birds’ population in the various communities around Kakum National Park, p-value>0.05.

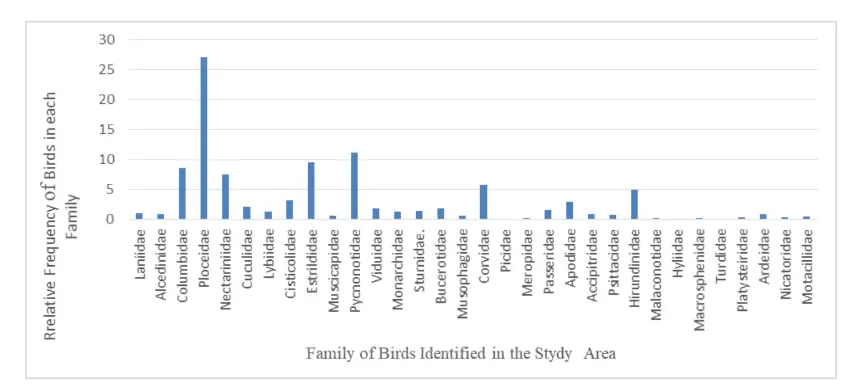

3.2. RALATIVE ABUNDANCE OF BIDS FAMILIES

The family Ploceldae were abundance in the study area with relative frequency of 27.203, Pycnonotidae recorded the second highest with relative frequency of 11.121 followed by Estrildidae and Columbidae of 9.581 and 8.554 relative frequency respectively. Picidae, Hyliidae and Turdidae recorded the least relative frequency of 0.0855. The table 4 below, shows the families of birds and their relatively abundance in the study area.

4.0. DISCUSSION

Kakum Conservation area lies in the Upper Guinea forest zone of southern Ghana which serves as a habitat for over 300 different species of birds (Eggert and Woodruff, 2003). A total of 1169 individual birds which represent 102 species and 32 families were observed and identified in the Study Area, Table 1.

Table 1: Categories of feeding guilds, families and numbers of individual sightings of the bird species

| CATEGORIES | FAMILY | SPECIES | NUMBER |

| Granivore Subtotal | Ploceidae | Yellow mantled widow bird | 11 |

| weaver Village | 94 | ||

| Estrildidae | Bare-breasted fire finch | 2 | |

| Chesnut breasted nigrita | 5 | ||

| Black-bellied seed cracker | 1 | ||

| Black and white mannikins | 45 | ||

| Passeridae | Passeridae | 19 | |

| Columbidae 4 | Red eyed-dove | 10 | |

| River ramped dove 9 | 1 188 | ||

| Insectivores | Cuculidae | African emerald cuckoo | 1 |

| Klass cuckoo | 7 | ||

| Dedric cuckoo | 3 | ||

| Senegal coucal | 14 | ||

| Cisticolidae | Tawny frank prinia | 17 | |

| Grey-backed camoroptera | 13 | ||

| Yellow-browed camoroptera | 1 | ||

| Red-faced cisticola | 7 | ||

| Muscicapidae | Dusky blue flycatcher | 1 | |

| Blue-shoulders robin-chatt | 1 | ||

| Grey-throated tit-flycatcher | 5 | ||

| Monarchidae | Blue-headed crested flycatcher | 7 | |

| Red-bellied paradise flycatcher | 2 | ||

| Paradise flycatcher | 6 | ||

| Picidae | Buff-spotted woodpecker | 1 | |

| Meropidae | Black bee-eater | 3 | |

| Apodidae | Little swift | 34 | |

| Hyliidae | Green hylia | 1 | |

| Macrosphenidae | Kemps long bill | 1 | |

| Green crombec | 2 | ||

| Turdidae | African thrush bird | 1 | |

| Platysteiridae | Chestnut wattle-eye | 4 | |

| Ardeidae | Cattle egret | 9 | |

| Little egret | 1 | ||

| Nicatoridae | Barn swallow | 4 | |

| Hirundinidae | Press swift swallow | 19 | |

| Common house matin | 16 | ||

| Western nicator | 22 | ||

| Ploceidae | Black-necked weaver | 23 | |

| Maxwell black weaver | 68 | ||

| Violet black weaver | 90 | ||

| Red-vinted malimbe | 5 | ||

| Red-headed malimbe | 1 | ||

| Pycnonodidae | Little greenbul | 5 | |

| Yellow wipsked greenbul | 1 | ||

| Alcedinidae | African dwarf kingfisher | 2 |

| Subtotal | Malacanotidae 17 | Black crown tchagra | 1 |

| Brown crown tchagra 38 | 2 401 | ||

| Frugivores Subtotal | Musophagidae | Western grey plantain eater | 2 |

| Bucerotidae | Pipping hornbill | 2 | |

| African pied hornbil | 19 | ||

| African grey hornbill | 1 | ||

| Pycnonodidae | Swamp palm bulbul | 17 | |

| Honeyguide greenbul | 1 | ||

| White-throated greenbul | 8 | ||

| Columbidae | African green pigeon | 57 | |

| Nicatoridae | Western nicator | 4 | |

| Lybiidae 6 | Nacked-faced barbet | 2 | |

| Yellow-spotted tinkerbird | 1 | ||

| yellow-fronted tinkerbird | 8 | ||

| Red-ramped tinker bird | 1 | ||

| Vieillot’s barbet 14 | 1 124 | ||

| Omnivores Subtotal | Pycnonotidae | Common garden bulbul | 84 |

| Slenderbill greenbul | 5 | ||

| Simple leaflove | 2 | ||

| Camaroon sombrine greenbul | 1 | ||

| Sturnidae | Splendid glossy starling | 17 | |

| Corvidae | Pied crow | 67 | |

| Psittacidae | Red-fronted parrot | 8 | |

| Estrildidae | Bronze mannikins | 35 | |

| Western bluebill | 1 | ||

| Motacillidae | Pied wagtail | 5 | |

| Musophagidae | Green turaco | 5 | |

| Columbidae | Blue-headed wood dove | 9 | |

| Tambourin dove | 4 | ||

| Blue-spotted wood dove | 8 | ||

| Nectriniididae 9 | Tiny sunbird | 7 | |

| Buff-throated sunbird | 4 | ||

| Superb sunbird | 7 | ||

| Olive bellied sunbird | 22 | ||

| Copper sunbird | 7 | ||

| Yellow-billed barbet 20 | 1 292 | ||

| Carnivores Subtotal | Accipitridae 1 | Yellow-billed kite | 4 |

| Lizard buzzard | 2 | ||

| African haired hawk 3 | 5 11 | ||

| Carnivores Insectivores | Alcedinidae | Malachite kingfisher | 6 |

| Shining blue kingfisher | 1 | ||

| Blue-breasted kingfisher | 1 | ||

| Laniidae | Common fiscal | 12 | |

| Frugivores Granivores | Columbidae | Grey-headed wood dove | 4 |

| Subtotal | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Nectarivores Subtotal | Nectriniididae 1 | Callard sunbird | 8 |

| Little green sunbird | 1 | ||

| Splendid sunbird | 9 | ||

| Green-headed sunbird 4 | 24 42 | ||

| Insectivores, Frugivores Subtotal | Lybiidae | Speckled tinkerbird | 3 |

| Estrildidea 2 | Grey headed nigrita | 1 | |

| Chesnut breasted nigrita 3 | 5 9 | ||

| Granivore, Insectivore Subtotal | Ploceidae | Black winged bishop | 24 |

| Estrildidae | Oranged-checked waxbill | 22 | |

| Red-fronted antpecker | 4 | ||

| Viduidae | Pintail whydah | 22 | |

| Columbidae 4 | Loughing dove 5 | 6 78 |

Table 2: Summary of number of birds in each community

| Community | Total No. of Species | Total No. of Birds |

| Bekawopa | 26 | 308 |

| Kobeda | 20 | 206 |

| Abrafo Odumase | 34 | 357 |

| Gyae Aware | 21 | 298 |

Table 3: ANOVA test of significance of birds within the communities.

| ANOVA | ||||||

| Source of Variation | SS | df | MS | F | P-value | F crit |

| Between Groups | 7024.5 | 3 | 2341.5 | 0.06346 | 0.97645 | 6.591382 |

| Within Groups | 147589 | 4 | 36897.25 | |||

| Total | 154613.5 | 7 |

The study indicated that the p-value of 0.976 from ANOVA test of significance, using Table 2, shows that there are no significant differences among the birds’ population in the study communities around Kakum National Park. (p-value>0.05).

Birds were categorized into several groups according to their foraging behavior. village weaver (Ploceus cucullatus) was abundance 94 followed by the violet black weaver (Ploceus nigerrimus) 90 and maxwell black weaver (Ploceus albinucha) 64 in that order being seed eater (granivores). They are common in the

study area because of the common traditional practice in the farming of corn and cereals such as rice maize etc. around the study area Kakum National Park. By germinating the seeds of trees, birds can contribute to the reforesting of deforested lands, diminishing the costs of restoration, Wunderle, 1997.

The fields create habitats that are used for foraging by other birds, as they dive down to where the layer of left-over harvested corn rests on the ground, they tear, shred, and churn up the pieces of straw looking for grain (Agyei-Ohemeng et al. 2017).

Figure 3: Foraging Mode and Number of Bird Species

Figure 4: Family of Bird Species Identified

The three most often observed species throughout the study were granivores, omnivores, and insectivores, in that order (Fig. 4). According to Erwin et al (2002), the study location, The Kakum Conservation Area, is a lush, wet, evergreen rain forest with dense foliage; insects and seeds (grains) prefer moist environments and dense foliage. Insectivore, omnivore and granivore birds were therefore observed in large numbers in and around Kakum National Park due to the existence of a significant food source.

According to Chettri et al. (2005), a habitat with dense vegetation, such as increased tree density and basal regions, influences the high existence of insects and seed; as a result, birds that feed on both insects and grains (Omnivores) were also abundant. Most birds get at least some of their nutrition from seed. Once more, studies by the Academy of Natural Sciences at Drexel University show that insectivorous birds get the majority of the water they require from their prey. Species from the family Pycnonotidae were recorded in four different feeding categories.

These species include Swamp Palm Bulbul being insectivores, Anropadus virens (Little Greenbul) a frugivore, and Calyptocichlaseri nanicatorchloris (Western Nicator) an omnivore. The Nicatorchloris (Western Nicator), according to Borrow and Demey (2010), has been proposed to be in a separate family (Nicatoridae) from the family Pycnocotidae.

Insectivores were identified to be the most diverse and numerous species in the research area, supporting Rajashekara and Venkatesha’s findings (2014). The occurrence and abundance of insectivorous species depend on the availability of a variety of food sources for adults and young as well as safe habitat for nesting and roosting in and near forest environment. On the one hand, insectivores in agricultural areas aid farms by reducing the number of insect pests in agricultural and habitation habitats, which raises the farms’ conservation value for birds and other animals. (Johnson et al. 2010).

The location of the study had one of the lowest densities of nectarines, therefore the timing of flowering and the presence of more nectarivores in the forest edge community may be to blame. According to Fleming & Sosa (1994), the structure and makeup of birds alter throughout time and space depending on the availability of food supplies. Variation is particularly obvious in bird species that eat patchy and transient food sources like nectar and fruit. As the level of land modification rose, Walterz et al. (2005) discovered fewer species of nectarivore in disturbed landscapes (farmland/settlement).

According to Cotton (2007), an increase in nectar availability is associated with an increase in the diversity and abundance of nectarivores. Because of their small size, nectarivores are challenging to monitor and are probably underappreciated in comparison to other guilds, according to Loiselle (1988). In addition, more bird species were discovered in the forest than in the disturbed region, according to Li et al. (2013).

The capture rate of frugivores in forests is typically higher during times when fruits are abundant, and the presence of some species belonging to the family Stunidae, Pycnonotidae is a perfect indicator of forest regeneration in semi-degraded/disturbed habitat such as a forest. Moegenburg and Levey (2003) note that the availability, abundance, and richness of fruiting plants are significant and associated with the diversity of frugivorous bird species and foraging. In the early stages of tropical forest succession and restoration, the tolerance of frugivore species to disturbed environments is crucial (Corlett, 2017).

According to Vallejo et al. (2006), existing green spaces must be preserved, and fruit trees must be added, to boost bird biodiversity. The Kakum environment will have a distinctive food web. A food web is a collection of organisms connected by interactions between consumers and resources, as well as predators and prey, and it represents all of the connected food chains in an ecological community.

With the presence of hawks, who eat tiny birds, flycatchers, and swifts, which eat flying insects, no food source will go to waste when taking into account the many foraging guild groups. The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List 2015-4 lists three of the species identified as being of global concern and vulnerable, which adds to the interest of the observations. Species that are considered vulnerable are those that are most likely to go extinct unless certain conditions are changed.

Numerous bird species’ distribution and abundance are influenced by the type of flora that makes up the majority of their habitats. Bird species abundance was highly correlated with vegetation traits, suggesting that areas with abundant plant life supported more birds. Because less resources are offered by this vegetation type within the sites, the relative low bird abundance in the highly disturbed areas compared to the other sites may be the result. A certain bird species may arise, increase or decline in population, and disappear when the habitat changes as vegetation changes along a long, complex geographic land environmental gradient. (Lee and Rotenberry, 2005)

The families ploceidae were recoded the higher number of individual species with the relative abundance of 27.203 and pycnonodidae recorded the second highers number of species in the study area, probably because the conditions needed by their members were available in the study area. Example, Village Weaver (Ploceus cucullatus) belonging to Ploceidae is the most abundant species in the study area due to the abundance of their food (Seed-eating birds).

The Common Bulbul (Pycnonotus barbatus) belonging to Pycnonotidae are also among the abundant species and are mostly found on farmlands due to the availability of food (Seeds) (Aziz et al. 2015). They were commonly observed on the ground and in grassy habitat where they would pick grains from plant sources such as maize and grasses. This shows that these two families are the most diverse in the study area.

Most plants completed their reproductive processes between the early months of the year. Also, harvesting of crops on farmlands started in January and there were much left-over foods on farmlands for birds to feed on (Agyei-Ohemeng et al. 2017).

Granivores are considered as pests by local farmers in the area (Kennedy, 2000). Moorcroft et al., (2002) concluded that fields left fallow after harvest support high densities of many species of granivorous birds, and they emphasized that variation in the abundance and availability of 41 weeds affects the diversity of granivorous species. Furthermore, the presence of a high diversity of granivores in a habitat indicated habitat disturbances (Gray et al. 2007).

5.0. CONCLUSION

The study gathered data on the structure and diversity of bird communities in and around Kakum National Park, and the findings imply that resource availability in a particular area or habitat determines the diversity, abundance, and distribution of birds. Nevertheless, birds can be divided into different groups based on their feeding habits. The study clearly shows that the majority of the bird species were found in places with dense vegetation and closed canopies. Since factors like fruits, seeds, flowers, and grains are present on healthy vegetation or habitat, this type of habitat promotes the growth of insects.

There are various bird species from various bird families that belong to various guilds of feeders. The Kakum National Park and Kakum Conservation Area have an extremely broad range of bird species, which is a sign of excellent ecological stability.

The study also adopted an ecological perspective by concentrating on the ways that birds assist humans by interacting with the environment through their foraging behaviors. It should be mentioned, however, that birds’ feeding habits often improve the ecosystem in ways that are ecologically beneficial. Nevertheless, if man made activities take hold, the diversity of bird species may fall.

Again, it may be said that viewing birds in local communities near protected areas has the greatest potential to inform residents and raise their knowledge of the value of bird ecology to local, national, and global biodiversity.

5.1. RECOMMENDATION

Promotion of and education in bird watching in communities around Kakum National park (KNP) has a considerable potential to produce money through the protection, conservation, and promotion of natural areas. This can boost the contribution of bird watching in rural communities.

The lack of understanding among the populace regarding the significance of birds in the ecosystem as pollinators, pest controllers, and environmental health indicators, must be promoted so that the municipality’s department of natural resources, land, and environment will educate the populace about conservation issues. This can help in the education on the importance of birds to the ecosystem.

To capture both nocturnal and diurnal bird species throughout various seasons of the year, an intense investigation and a survey of a comparable nature should be conducted. This could aid in identifying the number of birds of international importance that are lacking from the research

In order to find the best period for bird viewing, similar research comparing bird species populations during the rainy and dry seasons should be conducted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Our greatest gratitude goes to God Almighty for his blessings and granting us life full of strength throughout this work. We are immensely grateful for the invaluable contributions of the staff of Kakum National Park and the Abrafo community. Without their collaboration and support, this work would not have been possible. We feel privileged to have had the opportunity to learn from their expertise and share their stories. Our sincere thanks go out to each and every individual who has played a part in making this article a reality.

APPENDIX

Categorization of birds and their ecological status in Kakum National Park

| Granivore | Scientific name | Family | Ecological status |

| Yellow-Mantled Widow Bird | Euplectes macroura | Ploceidae | Lc |

| Village Weaver | Ploceus cucullatus | Ploceidae | Lc |

| Bar-Breasted Fire Finch | Lagonosticta rufopicta | Estrildidae | Lc |

| Chesnut Breasted | Nigrita bicolor | Estrildidae | Lc |

| Black-Bellied Seed Cracker | Pyrenestes ostrinus | Estrildidae | Lc |

| Black and White Mannikins | Spermestes bicolor | Estrildidae | Lc |

| Northern Grey-Headed Sparrow | Passer griseus | Passeridae | Lc |

| Red Eyed-Dove | Streptopelia semitorquata | Columbidae | Lc |

| River Ramped Dove | Spilopelia chinensis | Columbidae | Lc |

| Insectivores | Scientific name | Family | Ecological status |

| African Emerald Cuckoo | Chrysococ cyxcupreus | Cuculidae | Lc |

| Klass Cuckoo | Chrysococ cyxklaas | Cuculidae | Lc |

| Diedric Cuckoo | Chrysococ cyxcaprius | Cuculidae | Lc |

| Senegal Coucal | Centropus senegalensis | Cuculidae | Lc |

| Tawny-Franked Prinia | Prinia subflava | Cisticolidae | Lc |

| Grey-Backed Camoroptera | Camaroptera brevicaudata | Cisticolidae | Lc |

| Yellow-Browed Camoroptera | Camaroptera superciliaris | Cisticolidae | Lc |

| Red-Faced Cisticola | Cisticola erythrops | Cisticolidae | Lc |

| Dusky Blue Flycatcher | Muscica pacomitata | Muscicapidae | Lc |

| Blue-Shoulders robin-Chatt | Cossypha cyanocampter | Muscicapidae | Lc |

| Grey-Throated Tit-Flycatcher | Myioparus griseigularis | Monarchidae | Lc |

| Blue-Headed Crested Flycatcher | Trochocer cusnitens | Monarchidae | Lc |

| Red-Bellied Paradise Flycatcher | Terpsiphone rufiventer | Monarchidae | Lc |

| Paradise Flycatcher | Terpsiphone | Monarchidae | Lc |

| Buff-Spotted Woodpecker | Campethera nivosa | Pecidae | Lc |

| Black Bee-Eater | Merop sgularis | Meropidae | Lc |

| Little Swift | Apus affinis | Apodidae | Lc |

| Green Hylia | Hylia prasina | Hyliidae | Lc |

| Kemps Long Bill | Macrosphenus kempi | Macrosphenidae | Lc |

| Green Crombec | Sylvietta virens | Macrosphenidae | Lc |

| African Thrush Bird | Turdus pelios | Turdidae | Lc |

| Chest nut wattle-Eye | Platysteira castanea | Platysteiridae | Lc |

| Cattle Egret | Bubulcus ibis | Ardeidae | Lc |

| Little Egret | Egretta garzetta | Ardeidae | Lc |

| Western Nicator | Nicator chloris | Nicatoridae | Lc |

| Barn Swallow | Hirundo rustica | Hirundinidae | Lc |

| Press Swift Swallow | Hirundinidae | Lc | |

| Common House Matin | Delichon urbicum | Hirundinidae | Lc |

| Black-Necked Weaver | Ploceus nigricollis | Ploceidae | Lc |

| Maxwell Black Weaver | Ploceus albinucha | Ploceidae | Lc |

| Violet Black Weaver | Ploceus nigerrimus | Ploceidae | Lc |

| Red-Vinted Malimbe | Malimbus scutatus | Ploceidae | Lc |

| Red-Headed Malimbe | Malimbus rubricollis | Ploceidae | Lc |

| Little Greenbul | Eurillas virens | Pycnonodidae | Lc |

| Yellow Wipsked Greenbul | Eurillas latirostris | Pycnonodidae | Lc |

| African Dwarf Kingfisher | Ispidina lecontei | Alcedinidae | Lc |

| Black Crown Tchagra | Tchagra senegalus | Malacanotidae | Lc |

| Brown Crown Tchagra | Tchagra australis | Malacanotidae | Lc |

| Frugivores | Scientific name | Family | Ecological status |

| Western Grey Plantain Eater | Crinifer piscato | Musophagidae | Lc |

| Pipping Hornbill | Bycanistes fistulator | Bucerotidae | Lc |

| African Pied Hornbill | Lophoceros fasciatus | Bucerotidae | Lc |

| African Grey Hornbill | Lophoceros nasutus | Bucerotidae | Lc |

| Swamp Palm Bulbul | Thescelocichla leucopleura | Pycnonotidae | Lc |

| Honeyguide Greenbul | Baeopogon indicator | Pycnonotidae | Lc |

| White-Throated Greenbul | Phyllastrephus albigularis | Pycnonotidae | Lc |

| African Green Pigeon | Treron calvus | Culumbidae | Lc |

| Western Nicator | Nicator chloris | Nicatoridae | Lc |

| Nacked-Faced Barbet | Gymnobucco calvus | Lybiidae | Lc |

| Yellow-Spotted Tinkerbird | Pogoniulus chrysoconus | Lybiidae | Lc |

| Yellow-Fronted Tinkerbird | Pogoniulus chrysoconus | Lybiidae | Lc |

| Red-Ramped Tinker Bird | Pogoniulus atroflavus | Lybiidae | Lc |

| Vieillot’s Barbet | Lybius vieilloti | Lybiidae | Lc |

| Omnivores | Scientific name | Family | Ecological status |

| Common Garden Bulbul | Pycnonotus barbatus | Pycnonodidae | Lc |

| Slenderbill Greenbul | Stelgidillas gracilirostris | Pycnonodidae | Lc |

| Simple Leaflove | Chlorocichla simplex | Pycnonodidae | Lc |

| Cameroon Sombrine Greenbul | Andropadus importunus | Pycnonodidae | Lc |

| Splendid Glossy Starling | Lamprotornis splendidus | Sturnidae | Lc |

| Pied Crow | Corvus albus | Corvidae | Lc |

| Red-Fronted Parrot | Poicephalus gulielmi | Psittacidae | Lc |

| Bronze Mannikins | Spermestes cucullata | Estrildidae | Lc |

| Western Bluebill | Spermophaga haematina | Estrildidae | Lc |

| Pied Wagtail | Motacilla alba | Motacillidae | Lc |

| Green Turaco | Tauraco persa | Musophagidae | Lc |

| Blue-Headed Wood Dove | Turtur brehmeri | Columbidae | Lc |

| Tambourin Dove | Turtur tympanistria | Columbidae | Lc |

| Blue-Spotted Wood Dove | Turtur afer | Columbidae | Lc |

| Tiny Sunbird | Cinnyris minullus | Nectriniididae | Lc |

| Buff-Throated Sunbird | Chalcomitra adelberti | Nectriniididae | Lc |

| Superb Sunbird | Cinnyris superbus | Nectriniididae | Lc |

| Olive Bellied Sunbird | Cinnyris chloropygius | Nectriniididae | Lc |

| Copper Sunbird | Cinnyris cupreus | Nectriniididae | Lc |

| Yellow-Billed Barbet | Trachyphonus purpuratus | Lybiidae | Lc |

| Carnivores | Scientific name | Family | Ecological status |

| Yellow-Billed Kite | Milvus aegyptius | Accipitridae | Lc |

| Lizard Buzzard | Kaupifalco monogrammicus | Accipitridae | Lc |

| African Haired Hawk | Polyboroides typus | Accipitridae | Lc |

| Nectarivores | Scientific name | Family | Ecological status |

| Callerd Sunbird | Hedydipna collaris | Nectriniididae | Lc |

| Little Green Sunbird | Anthreptes seimundi | Nectriniididae | Lc |

| Splendid Sunbird | Cinnyriscoccini gastrus | Nectriniididae | Lc |

| Green-Headed Sunbird | Cyanomitra verticalis | Nectriniididae | Lc |

| Insect-Frugivore | Scientific name | Family | Ecological status |

| Speckled Tinkerbird | Pogoniulus scolopaceus | Lybiidae | Lc |

| Grey Headed Nigrita | Nigrita canicapillus | Estrildidae | Lc |

| Chesnut Breasted Nigrita | Nigrita bicolor | Estrildidae | Lc |

| Insect-Granivores | Scientific name | Family | Ecological status |

| Black Winged Bishop | Euplectes hordeaceus | Ploceidae | Lc |

| Oranged-Checked Waxbill | Estrilda melpoda | Estrildidae | Lc |

| Red-Fronted Antpecker | Parmoptila rubrifrons | Estrildidae | NT |

| Pintail Whydah | Vidua macroura | Viduidae | Lc |

| Laughing Dove | Spilopelia senegalensis | Columbidae | Lc |

| Insect-carnivores | Scientific name | Family | Ecological status |

| Malachite Kingfisher | Corythornis cristatus | Alcedinidae | Lc |

| Shining Blue Kingfisher | Alcedoqua dribrachys | Alcedinidae | Lc |

| Blue-Breasted Kingfisher | Halcyon malimbica | Alcedinidae | Lc |

| Common Fiscal | Lanius collaris | Laniidae | Lc |

| Gran-Frugivores | Scientific name | Family | Ecological status |

| Grey-Headed Wood Dove | Leptotila plumbeiceps | Columbidae | Lc |

REFERENCES

Agyei-Ohemeng, J.; Danquah, E.; Adu Yeboah, B. Diversity and Abundance of Bird Species in Mole National Park, Damongo, Ghana. Journal of Natural Sciences Research, 2017, 7, 12, 20- 33.

Agyei-Ohemeng, J.; Obour, R.; Asamoah, F.B. Ecosystem Perspective Review on Climate Change and Visitor Impact on Boabeng Fiema Monkey Sanctuary, Ghana, 2017.

Allport, G.A. The Feeding Ecology and Habitat Requirements of Overwintering Western Taiga Bean Geese (Anser Fabalis Fabalis) (Doctoral dissertation, University of East Anglia), 1991.

Aziz, S.A.; Mc Conkey, K.R.; Tanalgo, K.; Sritongchuay, T.; Low, M.R.; Yong, J.Y.; Racey, P.A. The critical importance of Old World fruit bats for healthy ecosystems and economies. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 2021, 9, 641411.

Balmford, A.; Green, R.E.; Jenkins, M. Measuring the changing state of nature. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2003, 18(7), 326-330.

Birdlife International. Birdlife Data Zone. 2005, [online.] Available at www.birdlife.org/datazone/index.html.

Bird Life International. Digital distribution maps of the birds of the Western Hemisphere, version, 5. 2012.

Borges, S.H.; Cornelius, C.; Moreira, M.; Ribas, C.C.; Conh‐Haft, M.,; Capurucho, J. M.; Almeida, R. Bird communities in Amazonian white‐sand

vegetation patches: Effects of landscape configuration and biogeographic context. Biotropica, 2016, 48(1), 121-131.

Brockington, D.; Igoe, J. Eviction for conservation: a global overview. Conservation and Society, 2006, 424-470.

Chace, J.F.; Walsh, J.J. Urban effects on native avifauna: a review. Landscape and urban planning, 2006, 74(1), 46-69.

Chettri, N.; Deb, D.C.; Sharma, E.; Jackson, R. The relationship between bird communities and habitat. Mountain Research and Development, 2005, 25(3), 235-243.

Clayton, N. Ornithology: Feathered encounters. Cordell, H.K.; Herbert, N.G. The popularity of birding is still growing. Birding. February 2002. pp 54-61.

Corlett, R.T. Frugivory and seed dispersal by vertebrates in tropical and subtropical Asia: an update. Global Ecology and Conservation, 2017, 11, 1-22.

Daily, G.C. Introduction: what are ecosystem services. Nature’s services: Societal dependence on natural ecosystems, 1997, 1(1).

de Iongh, H.H.; van Weerd, M. The use of avian guilds for the monitoring of tropical forest disturbance by logging. Tropenbos International Wageningen, the Netherlands, 2006. `1-34.

Deikumah, J.P.; Kudom, A.A. Biodiversity status of urban remnant forests in Cape coast, Ghana. Journal of Science and Technology (Ghana), 2010, 30(3).

Dirzo, R.; Raven, P.H. Global state of biodiversity and loss. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 2003, 28(1), 137-167.

Eggert, L.S.; Eggert, J.A.; Woodruff, D.S. Estimating population sizes for elusive animals: the forest elephants of Kakum National Park, Ghana. Molecular ecology, 2003, 12(6), 1389-1402.

Ehrlich, P.R.; Wilson, E.O. Biodiversity studies: science and policy. Science, 1991, 253(5021), 758-762.

Erwin, R.M.; Conway, C.J.; Hadden, S.W. Species occurrence of marsh birds at Cape Cod National Seashore, Massachusetts. Northeastern Naturalist, 2002, 9(1), 1-12.

Gómez-Baggethun, E.; De Groot, R.; Lomas, P.L.; Montes, C. The history of ecosystem services in economic theory and practice: from early notions to markets and payment schemes. Ecological economics, 2010, 69(6), 1209-1218.

Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Tudor, M.; Doroftei, M.; Covaliov, S.; Năstase, A.; Onără, D.F.; Cioacă, E. Changes in ecosystem services from wetland loss and restoration: An ecosystem assessment of the Danube Delta (1960–2010). Ecosystem services, 2019, 39, 100965.

Gray, M.A.; Baldauf, S.L.; Mayhew, P.J.; Hill, J.K. The response of avian feeding guilds to tropical forest disturbance. Conservation Biology, 2007, 21(1), 133-141.

Green, A.J.; Elmberg, J. Ecosystem services provided by waterbirds. Biological reviews, 2014, 89(1), 105-122.

Greenwood, K.; Rigby, E.; Laves, G.; Moscato, V.; Carter, J.; Tindale, N. Pilot study of aquatic weed dispersal by waterbirds in South-East Queensland. Sunbird: Journal of the Queensland Ornithological Society, 2007, 37(1), 37-49.

Hawthorne, W.D.; Abu Juam, M. Forest Protection in Ghana. Forest Inventory and Management Project. Planning Branch. Forestry Department, Kumasi, Ghana, 1993.

Honey, M. Ecotourism and sustainable development. Who owns paradise?, 1999.

International Institute for Environment, & Great Britain. Overseas Development Administration. Environmental Synopsis of Ghana. International Institute for Environment and Development, 1992.

Isaac, R.K.; Hall, C.M.; Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Palestine as a tourism destination. In The politics and power of tourism in Palestine, 2015, (pp. 31- 50).

Routledge. IUCN/PACO. Parks and reserves of Ghana: Management effectiveness assessment of protected areas. Ouagadougou, BF: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources/Program on African Protected Areas and Conservation (IUCN/PACO), 2010.

Ives, C.D.; Giusti, M.; Fischer, J.; Abson, D.J.; Klaniecki, K.; Dorninger, C.; Von Wehrden, H. Human– nature connection: a multidisciplinary review. Current opinion in environmental sustainability, 2017, 26, 106-113.

Jenkins, J. The meaning of expressed emotion: Theoretical issues raised by cross-cultural research. American journal of psychiatry, 1992, 149(1), 9-21.

Johnson, M.D.; Kellermann, J.L.; Stercho, A.M. Pest reduction services by birds in shade and sun coffee in Jamaica. Animal conservation, 2010, 13(2), 140-147.

Kennedy, R.; Gonzales, P.C.; Dickinson, E.; Miranda Jr, H.C.; Fisher, T.H.A guide to the birds of the Philippines. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Khan, S.U.; Gurley, E.S.; Gerloff, N.; Rahman, M.Z.; Simpson, N.; Rahman, M.; Luby, S.P. Avian influenza surveillance in domestic waterfowl and environment of live bird markets in Bangladesh, 2007–2012. Scientific reports, 2018, 8(1), 1-10.

Kong, F.; Yin, H.; Nakagoshi, N.; Zong, Y. Urban green space network development for biodiversity conservation: Identification based on graph theory and gravity modeling. Landscape and urban planning, 2010, 95(1-2), 16-27.

Kronenberg, J. Environmental impacts of the use of ecosystem services: a case study of birdwatching. Environmental Management, 2014, 54, 617-630.

Laurance, W.F.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Vasconcelos, H.L.; Bruna, E.M.; Didham, R.K.; Stouffer, P.C.; Sampaio, E. Ecosystem decay of Amazonian forest fragments: a 22‐year investigation. Conservation biology, 2002, 16(3), 605-618.

Lee, P.Y.; Rotenberry, J.T. Relationships between bird species and tree species assemblages in forested habitats of eastern North America. Journal of Biogeography, 2005, 32(7), 1139- 1150.

Lindenmayer, D.B.; Fischer, J. Habitat fragmentation and landscape change: an ecological and conservation synthesis. Island Press, 2013.

Loiselle, B.A. Bird abundance and seasonality in a Costa Rican lowland forest canopy. The Condor, 1988, 90(4), 761-772.

Lundberg, J.; Moberg, F. Mobile link organisms and ecosystem functioning: implications for ecosystem resilience and management. Ecosystems, 2003, 6(1), 0087-0098.

Ma, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Fu, X. The rapid development of birdwatching in mainland China: a new force for bird study and conservation. Bird conservation international, 2013, 23(2), 259-269.

Mace, G.M.; Collar, N. J.; Gaston, K.J.; Hilton‐Taylor, C. R.A.I.G.; Akçakaya, H.R.; Leader‐Williams, N.I.G.E.L.; Stuart, S.N. Quantification of extinction risk: IUCN’s system for classifying threatened species. Conservation biology, 2000, 22(6), 1424-1442.

Millennium ecosystem assessment, M.E.A. Ecosystems and human well-being, 2005, 5, 563.

Washington, DC: Island press. Moegenburg, S.M.; Levey, D.J. Do frugivores respond to fruit harvest? An experimental study of short‐term responses. Ecology, 2003, 84(10), 2600-2612.

Moorcroft, D.; Whittingham, M.J.; Bradbury, R.B.; Wilson, J.D. The selection of stubble fields by wintering granivorous birds reflects vegetation cover and food abundance. Journal of Applied Ecology, 2002, 535-547.

Moss, M.L.; Bowers, P.M. Migratory bird harvest in northwestern Alaska: A zooarchaeological analysis of Ipiutak and Thule occupations from the Deering Archaeological District. Arctic Anthropology, 2007, 44(1), 37-50.

Peres, C.A. Synergistic effects of subsistence hunting and habitat fragmentation on Amazonian forest vertebrates. Conservation biology, 2001, 15(6), 1490-1505.

Peres, C.A.; Palacios, E. Basin‐wide effects of game harvest on vertebrate population densities in Amazonian forests: Implications for animal‐ mediated seed dispersal. Biotropica, 2007, 39(3), 304-315.

Podulka, S.; Rohrbaugh, R.W.; Bonney, R. Handbook of bird biology. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2004. Raffaelli, D. How extinction patterns affect ecosystems. Science, 2004, 306(5699), 1141- 1142.

Rajashekara, S.; Venkatesha, M.G. Insectivorous bird communities of diverse agro-ecosystems in the Bengaluru region, India. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies, 2014, 2(5), 142-155.

Reed, J.M. Using statistical probability to increase confidence of inferring species extinction. Conservation biology, 1996, 10(4), 1283-1285.

Root, R.B. The niche exploitation pattern of the blue gray gnatcatcher. Ecological monographs, 1967, 37(4), 317-350.

Sekercioglu, C.H. Impacts of birdwatching on human and avian communities. Environmental conservation, 2002, 29(3), 282-289.

Sekercioglu, C.H. Increasing awareness of avian ecological function. Trends in ecology & evolution, 2006, 21(8), 464-471.

Symes, W.S.; Edwards, D.P.; Miettinen, J.; Rheindt, F. E.; Carrasco, L.R. Combined impacts of deforestation and wildlife trade on tropical biodiversity are severely underestimated. Nature communications, 2018, 9(1), 4052.

Tewksbury, J.J.; Anderson, J.G.; Bakker, J.D.; Billo, T.J.; Dunwiddie, P.W.; Groom, M.J.; Wheeler, T.A. Natural history’s place in science and society. Bio Science, 2014, 64(4), 300-310.

Wellington, H.N.A. Abrafo-Odumase: A case study of rural communities around Kakum conservation area. Kumasi: Department of Architecture and Planning, University of Science and Technology, 1998.

Wenny, D.G.; Devault, T.L.; Johnson, M.D.; Kelly, D.; Sekercioglu, C.H.; Tomback, D.F.; Whelan, C.J. The need to quantify ecosystem services provided by birds. The auk, 2011, 128(1), 1-14.

Whelan, C.J.; Şekercioğlu, Ç.H.; Wenny, D.G. Why birds matter: from economic ornithology to ecosystem services. Journal of Ornithology, 2015, 156(1), 227-238.

Whelan, C.J.; Wenny, D.G.; Marquis, R.J. Ecosystem services provided by birds. Annals of the New York academy of sciences, 2008, 1134(1), 25- 60.

Wunderle Jr, J.M. The role of animal seed dispersal in accelerating native forest regeneration on degraded tropical lands. Forest ecology and management, 1997, 99(1-2), 223-235.